Pandemic Response is a Defense Game, the U.S. is Playing Offense

By Meril Pothen, MPP

Like many American kids in the suburbs, I grew up playing soccer. As a defensive fullback, I stood guard and enviously watched my midfielder and forward teammates attempt dramatic plays and exciting shots on the other end of the field. Playing defense wasn’t flashy. But, when a swarm of players came barreling towards our goal, no amount of offensive panache could save us. What could mitigate a goal was my defense teammates and I operating in lockstep, diffusing the pressure and dampening the other team’s momentum.

While the COVID-19 pandemic is clearly higher stakes than my childhood soccer games, the strategy is similar. When faced with a new and aggressive opponent, a strong defense can hold off losses while an offensive play is developed, tested, and deployed. Although vaccine and treatment development are incredibly important in the fight against COVID-19, they are not an effective first line response. As the U.S. approaches 2 million cases and 112,000 deaths, we must address where our health care system is failing Americans during this pandemic to ensure we’re better prepared for the next one.

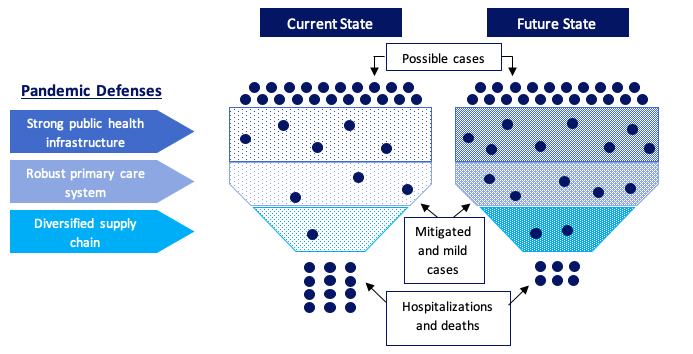

Pandemic response for a novel disease can be thought of as a layered filter, with each layer “catching” cases to reduce the number of hospitalizations and deaths. An effective pandemic response“filter” for the health care system consists of a well-funded public health infrastructure, a robust primary care system, and a diversified supply chain (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Pandemic Response Filter

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. revealed gaps in our defenses, resulting in fewer prevented and mild cases and more hospitalizations and deaths. The image on the right represents a stronger future state than our status quo, where gaps in our public health, supply chain, and primary care defenses are filled and able to “catch” more cases before they become severe and/or end in death. Source: Author.

Strong Public Health Infrastructure

The nation’s public health infrastructure is an essential first layer of defense during a pandemic, providing surveillance, education, and contact tracing support. Despite evidence showing a median 14:1 return on investment for public health initiatives in high income countries, public health is chronically underfunded at the federal, state, and local level. In 2018, only $286 of the more than $11,000 spent on health care per person that year went to public health. The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) budget has fallen by 10% over the past decade and the CDC’s funding to state and local governments for emergency preparedness dropped 33% from FY03-FY19. Cuts have contributed to over 55,000 eliminated positions at local health departments from 2007-2018.

Under-resourced public health departments cannot build the infrastructure needed to combat health crises like COVID-19. As shown by emergency funding for Ebola, Zika, the opioid epidemic, and now COVID-19, systemically under-resourced public health systems do not have the structures in place to most effectively use surge funding. Instead of a reactive and erratic approach to funding, the U.S. must commit to sustained, stronger investment in our public health system.

Robust Primary Care System

When health care providers began canceling appointments and services to prevent COVID-19 transmission, elective procedures and in-person visits dropped by 70-80%.This drastic drop in volume was a serious hit to provider revenues. Although hospitals have received advanced payments to smooth revenue losses, there have been no specific disbursements for primary care.

When well-resourced during an outbreak, primary care can triage and test, educate patients and family members, and support epidemiological surveillance efforts. Unfortunately, the American primary care system’s potential is hindered by clinician burnout, workforce shortages, and low investment (5% of total medical spending).

A reliable revenue stream that disconnects payment from volume can ease shocks for primary care providers during a crisis. Alternative payment models(APM), like Comprehensive Primary Care Plus and Primary Care First, pay providers PMPM (per member per month) fees for every patient they are responsible for, as long as specific outcome and quality metrics are met. This arrangement provides predictable revenue, relieves pressure for volume-based care, and grants flexibility in care plans.

An APM for community health centers serving low-income and vulnerable populations would be particularly effective in pandemic preparedness. It is well-established that COVID-19 disproportionately affects communities of color. These communities have been systematically disenfranchised and often live in conditions that prevent effective distancing, are more likely to be essential workers and have inadequate sick leave, and more often uninsured with less access to quality health care(see Brown and Xie, Holtzman, Nikpour, and Brown, and Durbha, Holtzman, and Matula reflections).Population-based and lump-sum payments to invest in community health workers, culturally-sensitive and relevant education, and non-medical needs can lessen the impact of a new infectious disease on the community.

Diversified Supply Chain

A final early COVID-19 challenge was shortages of essential personal protective equipment (PPE), medical equipment, testing supplies, and medications. Although hospitals and universities are are still rationing and reusing single-use PPE. Nearly 600 health care workers on the front line have died from COVID-19 since the pandemic began.

Shortages in COVID-19 testing supplies slowed down the country’s testing rate, risking increased community spread. Heightened demand for antibiotics, hydroxychloroquine, and other medications left hospitals scrambling and those with chronic conditions unable to fill needed prescriptions.

To keep costs low, U.S. health care supply chains are lean and narrow. Specific countries or regions are often the sole producer of a certain health care good. Test swabs, for example, are mainly made in Northern Italy. Face masks are largely sourced from China, and most active ingredients for medicines are produced in China and India.

Health care leaders must diversify the health care supply chain to prevent future shortages during a crisis. While single-source supply chains provide tempting low prices, bringing on additional domestic and international suppliers allows for are liable supply and an ability to scale up production when needed. This reform should also move upstream, diversifying raw material producers for supplies.

In addition to increasing supply, the federal government should play a larger role in coordinating procurement and distribution of supplies during a crisis. Throughout this pandemic, states, hospitals, and universities have created informal networks to ship supplies to hard-hit regions. Federal support to formalize this coordination will prevent competition and better ensure distribution based on need.

Looking Forward

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that a rapid, defensive response is the best tactic to decrease infections and deaths.To be better prepared for the next outbreak, the U.S. must make reforms now to develop a well-resourced public health infrastructure, robust primary care, and diversified supply chain. Like playing defense on the soccer team, this work often goes unheralded and seems banal in comparison to vaccine and treatment development. But, when a new opponent comes hurtling towards our family, friends, and communities, it will be the only barrier standing in the way. For our future, let’s ensure that defense is strong.

About the Author

Meril Pothen, MPP, recently graduated from the Duke University School of Public Policy in May 2020 and was a Margolis Scholar in Public Policy.